back to Digital Feudalism /// Deutsch / English

Survival After Wage Labor: Strategies for Transitioning to the Ownership Economy

“Soon, wealth accumulation will no longer be possible through labor, but through correct positioning within the monetary redistribution system”

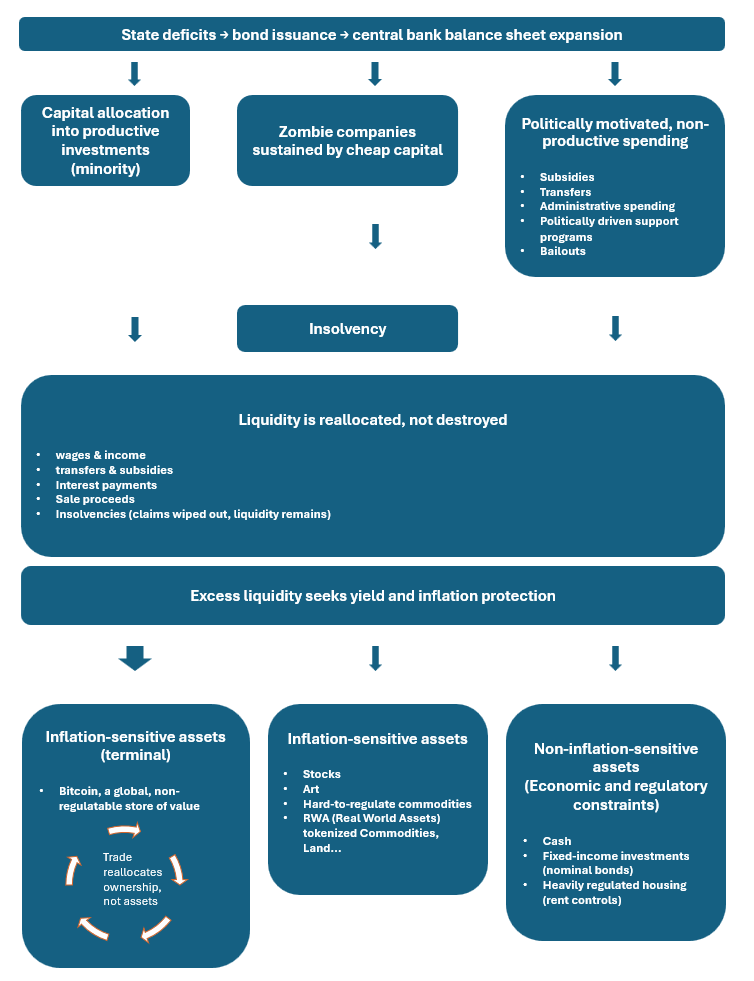

The following considerations are not based on individual choices or personal preferences, but on the systemic effects of modern monetary and fiscal policy. To illustrate these effects, the introductory graphic traces the path of excess liquidity through today’s economic system—from money creation to wealth concentration. This mechanism is central because labor income is steadily losing its role as the primary source of economic security and must be replaced by other forms of income and value preservation. The graphic serves as a high-level overview of a process that will be explained in detail below.

In the age of artificial intelligence and structurally declining demand for human labor, the core challenge is no longer education, but economic survival. Large segments of the population can no longer secure their livelihoods sustainably through wage labor alone. Income derived from work is losing its function as a stable foundation for long-term economic security.

This article outlines the strategies individuals must pursue during the transition from classical wage labor to a future system in which income is increasingly decoupled from work and supplemented or replaced by a production-based Universal Basic Income (UBI). The objective is to exit wage dependency before the system transition is complete and to move through ownership of productive assets into the ownership layer that controls value chains and retains privileges beyond the scope of a production-based UBI.

Until recently, such strategies were largely confined to financially educated elites. As wage labor is structurally eroded, however, they are becoming unavoidable even for performance-oriented and upward-mobile segments of the population.

The mechanism of wealth accumulation described here can already be observed empirically in economic developments, political decisions, and individual life trajectories. What follows is a systematic reconstruction of this mechanism.

Two Paths After the Decline of Wage Labor

With the structural elimination of wage labor, there are two fundamental ways to accumulate wealth:

(1) Ownership of productive value creation and its scaling, i.e. direct participation in future value chains.

(2) Ownership of inflation-sensitive assets, which absorb monetary expansion within an inflationary monetary system and thereby preserve relative purchasing power compared to wage earners and cash holders, without directly controlling productive value creation

Path 1: Participation in Future Value Creation

The most direct route into the ownership layer is participation in future value creation. This can occur either through founding a business or through ownership stakes in existing companies.

Building a company represents the strongest form of this path, but also the most demanding. Requirements in terms of business model design, innovation, financing, and risk tolerance are substantial. As a result, this route is structurally unsuitable for the majority of the population.

Ownership through equities or private company shares lowers the formal barrier to entry. Publicly listed companies allow passive participation in established value chains and are therefore accessible to a broader group. Nevertheless, this path still requires specific capabilities—most notably analytical competence, discipline, and psychological resilience in the face of volatility.

Overall, ownership of productive value creation remains structurally constrained. It is scarce, time-dependent, and requires capital, informational advantages, and risk tolerance. For a minority, it enables ascent into the ownership layer. For most, it remains an indirect and limited form of access.

Path 2: Ownership of Inflation-Sensitive Assets

The second path is also non-trivial. Its underlying mechanism must first be understood and accepted, often in contradiction to conventional economic intuition. While it is less operationally demanding than building or owning productive enterprises, it requires the ability to recognize abstract monetary dynamics and to trust them over long time horizons.

At the same time, this path is the most broadly accessible. It does not rely solely on scarcity, but on ownership of assets capable of absorbing monetary expansion—assets that preserve relative purchasing power disproportionately compared to wage income or cash holdings.

Inflation in this context is not accidental. It emerges as a game-theoretically consistent outcome of the monetary and geopolitical strategies pursued by global powers such as the United States, China, and Russia. Inflation functions as a systemic overflow mechanism for the accepted side effects of aggressive strategies aimed at dominance, stability, and technological supremacy.

Monetary Policy as a Geopolitical Weapon (“The Winner Takes It All”)

In the struggle for global supremacy, artificial intelligence and robotics have become the central strategic industries. In particular, AI exhibits winner-take-all dynamics: an initial advantage can be amplified through scale effects, data accumulation, and capital concentration until a technological tipping point is reached, beyond which competitors can no longer catch up.

Major powers with the necessary technological, financial, and institutional capacity are fully aware of this dynamic. Competition is therefore not treated as incremental, but as existential. Side effects and collateral damage are accepted because success, from the perspective of these actors, more than compensates for the costs.

This strategy is not new. The United States has pursued variants of it since the 1970s, while China has applied it in a particularly concentrated form in recent years, for example, in the automotive and battery sectors.

The core logic is straightforward: produce globally competitive and potentially dominant products without knowing in advance which specific actors will succeed. The solution is a state-reinforced venture-capital model. Innovation is financed broadly and aggressively, underwritten by monetary sovereignty. Monetary expansion becomes a strategic instrument that enables many attempts, with the expectation that the resulting breakthrough—and its associated value creation—will remain within the issuing power’s sphere of influence.

Most participants fail. This is not a flaw, but a necessary feature of the system. A small number of winners achieve dominant positions and capture disproportionate value. From the state’s perspective, their success retroactively justifies the widespread misallocation of capital.

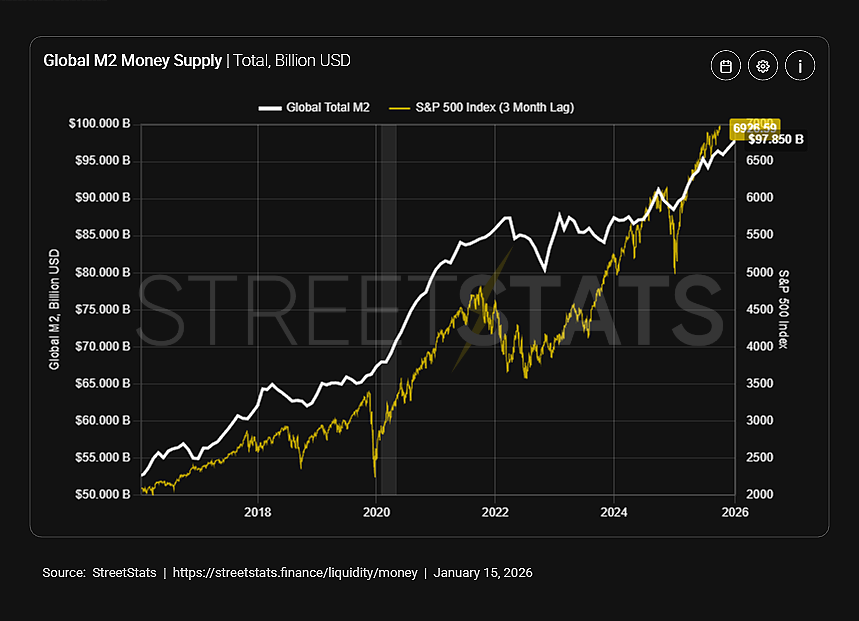

The outcome is a concentrated winner structure—and a massively expanded money supply. This monetary expansion is not an unintended by-product, but the predictable consequence of a strategy that deliberately finances many failures to produce a few structural winners.

After Consolidation: Where the Money Goes

Once consolidation occurs, the expanded money supply does not disappear. Systemically, it remains in only two functional locations:

1. Within value chains

- in successful firms

- in wages, margins, and investment budgets

- in state-linked or strategically protected sectors

→ This is where real economic activity continues and scales.

2. In inflation-sensitive stores of value

- assets that absorb monetary expansion

- mechanisms for preserving relative purchasing power

Money outside these two domains is gradually written off or loses value in real terms. No third stable state exists.

A Systemic Side Effect: Money Persists Regardless of Origin

A peculiar but systemically important consequence follows from this logic. Money introduced into the system through fraud or criminal activity does not vanish once such activities are uncovered. Legal claims may be reversed, but the money itself remains fully embedded in the monetary system.

Large-scale welfare fraud cases in the United States illustrate this mechanism clearly. These payments were financed through government spending and, ultimately, monetary expansion. When fraud is later exposed, legal penalties follow, but the issued money supply is not withdrawn. It has already dispersed throughout the system.

Crucially, allocation matters. Funds derived from fraud are rarely reinvested in visible, productive enterprises, where exposure risks are high. Instead, they tend to migrate into inflation-sensitive stores of value that offer anonymity, liquidity, and protection against devaluation.

As a result, even capital originating from illegal or illicit sources ultimately reinforces the same asset categories that absorb monetary expansion. Those positioned in such assets benefit indirectly and systemically from these flows—not as a moral endorsement, but as a mechanical outcome of the monetary system’s structure.

Inflation-Sensitive Assets

Not all assets can absorb inflation. Certain goods are politically and socially sensitive, including housing, food, and inputs critical to industrial production. Uncontrolled price increases in these areas threaten social stability, political legitimacy, and supply security.

Governments are therefore compelled to suppress price increases in these sectors through subsidies, regulation, price caps, or rent controls. These measures do not eliminate inflation; they merely displace it.

To absorb excess liquidity without triggering unrest, the system requires a monetary overflow valve. Inflation-sensitive assets fulfill this role precisely because their price movements are politically tolerable and do not directly undermine basic living conditions.

The effect is twofold: newly created money flows into these assets, and inflation that cannot be expressed in essential goods is redirected toward them.

The Ideal Overflow Valve: Bitcoin

Despite being widely discussed, the argument remains valid. At present, Bitcoin is the most effective monetary overflow valve.

Bitcoin is largely decoupled from existing real-economy dependencies, historical ownership hierarchies, and state-controlled pricing regimes. This makes it uniquely suited to absorb excess liquidity without destabilizing politically sensitive price structures or entrenched elites.

Bitcoin itself is not inflated. It absorbs inflation. Monetary expansion occurs within fiat systems; value preservation occurs outside them. Excess capital can flow into Bitcoin instead of driving up prices for housing, food, or strategic industrial inputs.

The growing institutional and governmental tolerance—particularly in the United States—suggests that this function is understood. Bitcoin is not actively managed as policy, but passively accepted as an external reservoir for excess liquidity.

Other inflation-sensitive assets exist, but few combine scarcity, global liquidity, political neutrality, and structural non-inflation in comparable form. Bitcoin is therefore not accidental, but functionally well-suited to its role.

The distributional outcome is mechanical rather than moral. Those positioned early or correctly benefit in relative terms; those who are not lose purchasing power. At the same time, the real economy may benefit from the monetary expansion that this mechanism enables.

How Much Bitcoin Is Enough?

Bitcoin’s price trajectory is likely to remain strong in the near future. The underlying process is not complete, and no structural saturation point has been reached. This is driven not only by Bitcoin’s role as an inflation absorber, but also by additional fundamental factors explored elsewhere (see energy-to-value.com).

For younger individuals, a large initial allocation is not required. What matters most is time and patience. Given the long-term nature of the system transition, even a modest but consistently held position can suffice to participate meaningfully.

Conclusion: Positioning Matters More Than Participation

As wage labor erodes and monetary dynamics evolve, neutrality disappears. Individuals, firms, and states must take positions. Inaction itself becomes an allocation choice— one that favors purchasing power loss.

The two paths outlined serve different functions.

Ownership of productive value creation confers power and control, but is elitist and limited.

Ownership of inflation-sensitive assets offers broad-based protection and remains the only realistic option for large segments of the population.

A production-based UBI may stabilize the system, but it does not replace ownership. It provides subsistence, not advancement, within an increasingly refeudalized economic order.

The decisive divide is therefore not between work and non-work, education and ignorance, or effort and indolence. It lies between ownership and non-ownership—a distinction rooted in monetary mechanics, not ideology.

The transition window is finite. Those who position themselves early preserve optionality. Those who do not are absorbed into the downstream distribution logic, regardless of effort or qualification.

Therefore:

“Wealth accumulation will no longer be possible through labor, but through correct positioning within the monetary redistribution system”

Published: 2026-01-17